Discussion with Jim Steranko

The place was an occurrence of the San Diego Comics Convention. I was an aspiring comics writer and had just graduated from the University of California at Santa Cruz by writing a senior thesis/essay about Appreciating Comics. A good part of the essay involved analyzing comics stories—studying the art and finding symbols in. the pictures and colors and shapes—combining the symbols into themes (as inspired by author and film instructor Janey Place). I wrote that sometimes the themes in the art are consistent with the story told in the words; sometimes not.

I was still bubbling with these ideas when I ran into Jim Steranko, ground-breaking writer/artist and publisher, in the Dealers’ Room. As we talked, Steranko became interested and wondered what visual analysis would reveal in two of his stories “At the Stroke of Midnight” and “Today Earth Died!”

Mark Clegg, a fellow UCSC alumni, creative collaborator and comics scholar, helped me scour the Dealers’ Room for copies of Tower of Shadows #1 and Strange Tales #168 (both published by Marvel Comics) and I spent the evening in our hotel room staring at those two stories and scribbling notes.

From “At the Stroke of Midnight” I came up with a theme involving objects becoming alive, living things becoming objects, and how the two get mixed. (My thoughts on “Today Earth Died” may be lost to history.) Armed with these ideas, I found Steranko in the Dealers’ Room again the next day and we started talking. The conversation was genial and lively, but bumpy, as we had different agendas.

In 1983, Mark published an innovative comics anthology called Dragon’s Teeth. He transcribed part of the conversation from a cassette tape to create a text piece for the anthology. That transcription is what follows…

JIM STERANKO: I wanted the readers to concentrate on the story, not on the graphic effects and things that I usually did, like on the Captain America strips and Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D., where all that "zap art" was very distracting. The story hardly mattered, the art was the star. Here the story was the star; the story was the main thing. The art was not too distracting although I did have a number of—let's call them effects--but I don't think they distracted from the story. I drew in a photographic style because I wanted the reader to believe this was the real thing, not just cartoon figures. You see they are very important in it.

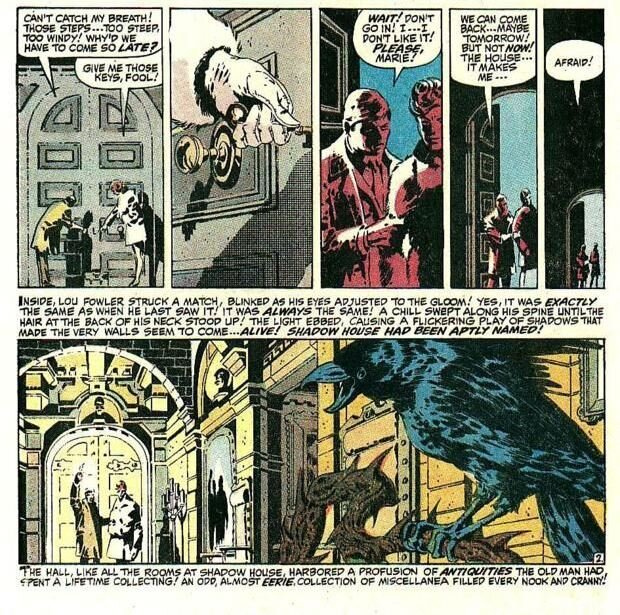

CHARLIE BOATNER: The characters are turned into objects by the stroboscopic effect. [Page 2/panels 1-4]

STERANKO: No, it's not a strobe effect. It's simply that the size of a panel is equated with the length of a shot, cinematically. Although this wouldn't be three separate shots, it would be one. I was trying to get a repetitious kind of an effect. I'm trying to develop characterization in the size of the panels.

BOATNER: Of course, I realize I'm reading things in. I felt in a way that was my job.

STERANKO: Oh yes, you're right.

BOATNER: The thing about a strobe is you have drawn someone frozen—the life is taken out of them. They're turned into just jerky images.

Of course, these stories are almost always some kind of retribution thing—the characters have killed someone, taken the life out of someone else so this is happening to them.

In the meantime the house is taking on a life and taking on imminence. In my thesis, I said that most comics do an incredible amount of emphasis on humanity, on the characters. In this story you go against that. For instance, in this sequence [2/7-9] ,you got the people receding and the background becoming larger. The people are practically gone in favor of stairways, racks, shadows. The door dwarfs them. Even the words reaffirm the house becoming a character. "The flickering play of shadows made the very walls seem to come alive" and in the panel underneath you have tiny characters and a large illustration of the house.

Page 2/panels 5 to 10, the house becomes a character

STERANKO: Well, that's true. Especially that shot. That bird right up front. You're trying to say that that house possesses a life of its own.

BOATNER: Right, and visually that's done very well. Here is a little more of the house taking center stage [4/4-7] . This strip is great, panel by panel.

STERANKO: Yes, it begins to take on life forms. I mean, everything is carved into live figures. It's meant to have a kind of life of its own.

BOATNER: Here, the objects take center stage, and seem to lock her in there. The panel border pins her like a butterfly [5/8,9].

STERANKO: Yeah, I wanted to get a kind of Vertigo, a tracking shot like Hitchcock does.

BOATNER: There's also a kind of Rope effect in here.

STERANKO: Yes, yes there is.

BOATNER: Where you start a little bit open, then everything starts narrowing in; people are crammed into the panels.

[A passerby joins the conversation briefly]

UNKNOWN: Even when the story was transformed for reproduction in a black and white magazine it wasn't exactly black and white.

STERANKO: Well, I think what we did was reproduce from stats.

UNKNOWN: Yeah, well I meant...

STERANKO: It was designed for color, it was meant to have color. I put the zip in, in the black and white version, in the magazine version. I preferred the color because I was able to do symbolic psychological things. Like, when I wanted real anger, I'd punch in a red panel [5/2], which, like here, is not very subtle, but then people don't think of those things.

UNKNOWN: You can have color with black and white beside it. The black and white really stands out because you can have zip on the wall and then black and white beside it.

STERANKO: That's why I did this, because I wanted all emphasis to be on the door, so I even knocked out all color on the people [5/4]. I mean, the door was the alive thing, that's the one that had the color. That's the kind of thing you're talking about.

Page 5/panels 2 to 6, color effects

BOATNER: And I like the objects through this that seem to be in middle life; things that were alive that are now objects: the raven, the skull, the frog.

STERANKO: This door is based on a Wendall Wetherland design [5/8]. It's positively alive unto itself. You wouldn't like to see that door at night, by itself.

BOATNER: No, no thanks.

STERANKO: Though it's not really a face, it's just leaves and other things.

BOATNER: So, the crime, having to do with objects, comes out on page six. We have here the memory which shows only a tiny silhouette, not very human [6/11]. Here we have a piece of wheel chair which is identified with a person [6/9]. And this was all in the name of money; taking life away from a person, then giving life or importance to these objects. This is even punched up about later in the dialogue, "losing their heads over money that way."

STERANKO: I wonder if I wrote that or Stan wrote that. I'm not sure which of us wrote that. We missed the panel…oh yeah, here it is, this page. I was trying to make it look like this was a real human being here. By the way, this was filmed—this entire story was put on film. John Carradine is the old man and this guy was John Fiedler, you know him?

BOATNER: No, I don't.

STERANKO: You ever see the movie 12 Angry Men? Courtroom drama. John Fiedler is this very mousey guy and he played that.

BOATNER: Right, right, of course.

Of course the old man is the other creature between life and death. Here you have a portrait that is alive of a man who was once dead. Here is a very interesting emphasis—if you have a choice of something to scream at—the old man (of course he is frightening because he might be a ghost) or the guillotine (which I would think they're actually afraid of)—it is him which causes the terror [7/1-4].

STERANKO: No, it isn't really. What they're afraid of is not the old man and not the guillotine, which sort of compounds the fear, but the fact that at the very end he raises his hand and points at them.

BOATNER: Just like in the painting?

STERANKO: Just like in the painting.

BOATNER: Okay, now, on the subject of characterization: You create a contradiction which is neat. In the dialogue you have this great conflict built up between the characters, as you say, between the mousey male and the dominating woman, and this is emphasized by their sizes (which seems clear enough, I wasn't even going to go into it). And yet nicely enough, visually, you contradict the conflict. I know in film language, when you want to show a division between people you show them separately in one-shots. [Mark Clegg notes: A "one-shot" has one character on the screen, a "two-shot" has two.] Your characters are shown most often together in two-shots which subtly marks them as two-of-a-kind, no matter how much they talk about how different they are. Here's a two-shot [2/7], here's another [3/10], and this is basically a two-shot if it wasn't for that panel line [3/8,9]. Even this, where he's wearing a sort of darkish coat and she's wearing a very light coat—this match works to cast his coat in practically the same color as hers which once again shows them for the same sort of person [3/10].

STERANKO: There's also like engulfing black, a very ominous somber feeling.

BOATNER: Right, and he's got this light lightening him up like he's on a police line-up [3/2,4]. So where he's talking like he certainly loved his uncle, this light is pointing out his guilt. I don't know what this is for symbolically, but I love the way this shows the match going out [3/11-13].

Page 3/panels 1 to 9, one-shots

STERANKO: I like this story. It had a lot of interesting things. It looks especially pleasing from this concept. Very subtle things for comics. I doubt if one out of a hundred readers really saw that figure and began to understand it.

BOATNER: Why are comics so often unsubtle?

STERANKO: Oh, because the market is the 10 year old.

BOATNER: Yet you can do layering of meaning. I expect a 10 year old would enjoy this also.

STERANKO: I did that with my SHIELD books. I consciously drew it on three levels. One for 7 year olds who didn't really care for reading and just wanted to look at the pictures, who could understand the story because of the pictures. I did it on another level for, say the 13 year old, who liked wild adventure and read it and this was just fantastic stuff. Then I did it for the 17 year old as satire. You know, I tried to fill all three functions.

BOATNER: It seems it should be possible. A good story should appeal to everybody.

STERANKO: When I do a story, my basic philosophy is that you can forget the story after you've read it. Forget the characters. Forget the plot. What I want to remain is the impact of the feeling of the story. You put it down and say "I was really moved by that story." I want you to remember the emotion, the impact that comes out of all the images and words. Forget the rest. If you do that I think you've got something there. It's like coming out of a theater after you've seen something like Star Wars or a film like It's a Wonderful Life by Frank Capra. I never want that film to end. I want it to go on. I know it's getting close to the three hour limit, I know it's got to end soon, but I don't want it to. I'm hoping, like, for a station break, and then it'll go on. That's the way I'd like my stories to be.

BOATNER: Oh, I forgot to mention this before when I was on the subject of the objects. It seems to happen a number of times in your work, the disembodied hand. You see who it belongs to, yet it goes around the panel so, like, his hand here almost becomes a candelabra or, or a gilt piece [4/1-3].

Page 4/panels 1 to 3, playing around with time

STERANKO: That's how I was tying this panel [4/1] with this one [4/3]. You see, this one had to do with the time reference of this one. This was real time [4/1] and this was real time [4/3], so by using the hand as a device, like a kind of framing device, it brought this panel [4/2] back into real time. Otherwise it would have gone into flashback, and we would have stayed in flashback. This was a device to bring it back into real time.

BOATNER: It was a kind of traveling shot.

STERANKO: Exactly, that's exactly what it was. This early shot right here [2/1-4] also was meant to be a traveling shot, because, although this is one complete background, they don't appear four times. This is a time reference, then the camera travels with them up the stairs.

Like you just said, the match goes out but here the match that he's holding goes out as he's speaking [3/11-13].

BOATNER: Each time, the characters are shown to be basically interchangeable. Like here, these panels are referenced to each other and the characters are drawn in the same sort of light. If it wasn't for the coloring and a little bit of hair you couldn't tell them apart.

STERANKO: Still, the color is telling you something. She's full of anger and hatred and he's very cowardly, very timid.

BOATNER: The best characterization has two things going on at once. Where you have the color and the dialogue dividing them, you have position on the page and lighting bringing them together.

This is where you got the coming together and separation both at once, pushed to the extreme. You got the violence of their interaction and yet visually they're melded together, like...

STERANKO: Like they're all part of the same arms and legs [6/7].

BOATNER: Right. Then as a final shot you got, "Then they began to scream," yet it's one image and I think it's both of them [7/6].

Page 7/panel 6

STERANKO: Well, of course it is. You can't even tell here who it is. If it's the man or the woman. there's no telling.

BOATNER: Right, so they shared the guilt and now they're sharing the punishment.

STERANKO: There was one line of dialogue that was changed. I think Stan put that in. I think there was one other one. This is the story I left Marvel over on account of they did some stupid things. I wanted to call it "The Lurking Fear of Shadow House;" he wanted to call it "Let Them Eat Cake;" so we settled on "At the Stroke of Midnight" and they changed two lines.

BOATNER: I'd like to know what they would have been. That line, the one that you said was changed, is obviously a "let's explain it to the kids" routine.

STERANKO: Yes, that wasn't in there at all. I'm not even sure that line was in there as they could see what was going on.